International Push for “Green Blockchain”

Crypto’s environmental bill is coming due. This piece pulls together how the IMF, UN bodies, activist NGOs, the EU, the United States and a widening group of governments are pivoting from observation to hard policy, from electricity-use surveys to outright PoW bans.

By tracing these converging moves and the incentives behind them, we show where regulation is headed next—and lay out what miners, investors and policymakers can do now to stay ahead of a greener, stricter crypto era.

Key Insights

- Crypto mining’s energy footprint is becoming a regulatory inevitability. IMF and EU data frameworks point toward a future where climate-aligned taxation and mandatory disclosures will reshape mining economics.

- The ESG narrative is expanding: from emissions to water, land, and social equity. UNU and NGO-led analyses emphasize that Bitcoin’s externalities disproportionately impact vulnerable geographies and ecosystems.

- While industry innovations (efficient chips, renewable siting, heat reuse) are emerging, they remain too niche to drive systemic change. Institutional capital and policy alignment are required to shift incentives and scale sustainable mining practices.

Section 1 - IMF: Correcting the Incentive Imbalance in Crypto Mining

Key message: Current mining economics reward energy use more than energy efficiency—this must be reversed with fiscal tools.

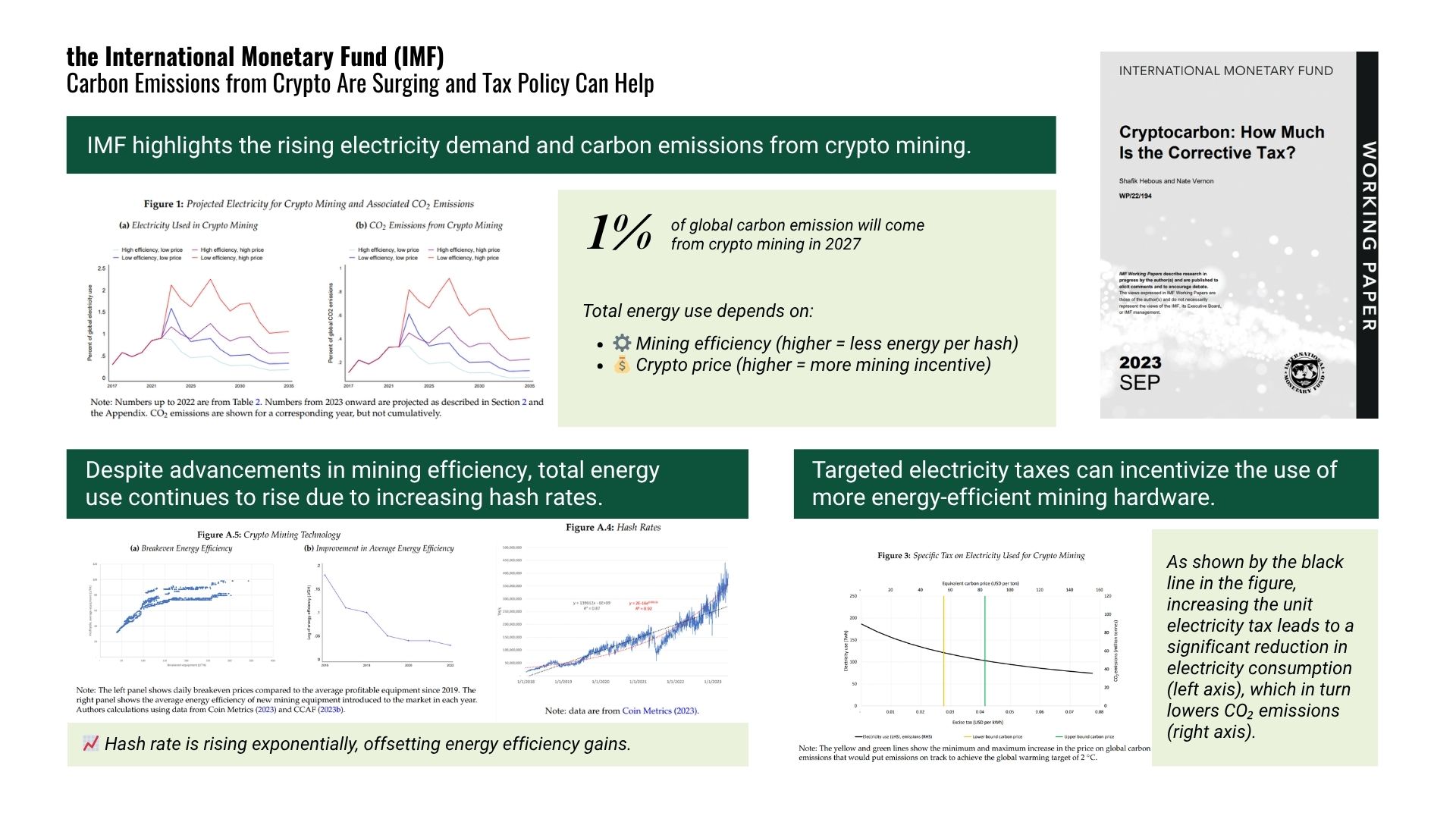

The IMF highlights a structural flaw in today’s crypto mining market: the absence of economic incentives to prioritize energy efficiency. When crypto prices rise, miners flood in, competing with increasingly powerful (and often less efficient) hardware to secure profits. Meanwhile, gains in mining efficiency—though technologically impressive—are routinely offset by this surge in total network activity. As a result, the global hash rate grows faster than efficiency improvements, and total electricity use continues to climb. The Fund estimates that, without policy intervention, crypto mining could contribute nearly 1% of global CO₂ emissions by 2027.

To change this trajectory, the IMF proposes targeted electricity taxes and dynamic carbon pricing. These instruments would increase the cost of energy-intensive mining strategies, creating clear financial advantages for operations that adopt low-emission power sources or highly efficient chips. The goal is not to suppress mining, but to rebalance incentives so that economic logic pushes miners toward cleaner, leaner practices—rather than rewarding sheer computational force.

Section 2 - UNU: Broadening the Lens Beyond Carbon

Key message: Bitcoin mining’s ecological harm extends far beyond carbon. It and disproportionately affects vulnerable countries.

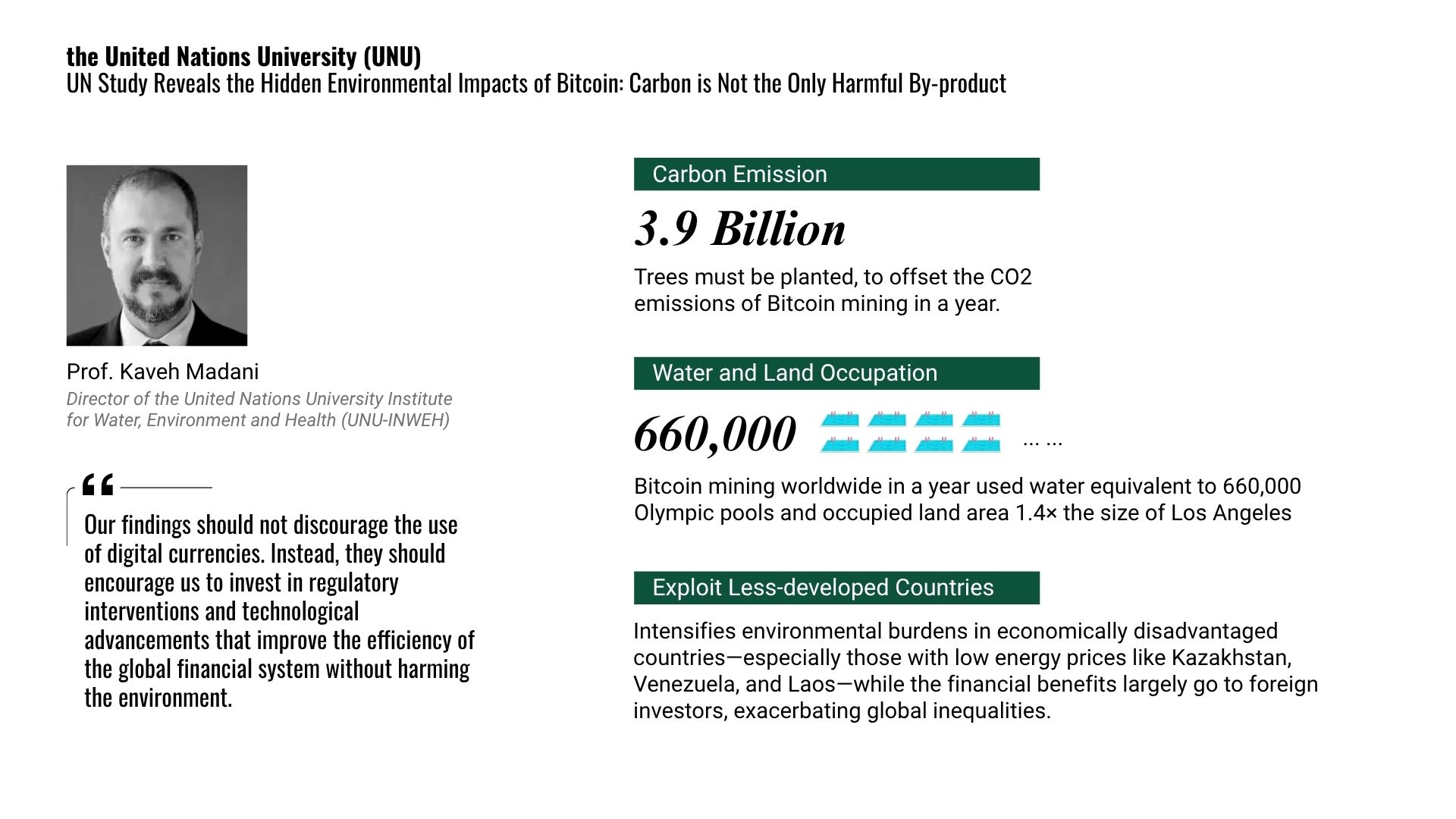

The United Nations University (UNU) expands the conversation from emissions to broader environmental and social costs. Its recent study shows that offsetting Bitcoin’s annual emissions would require planting nearly 4 billion trees, while its water use equals 660,000 Olympic swimming pools, and its land footprint spans 1.4 times the area of Los Angeles. These resource demands are the by-product of a system where energy consumption is not penalized, but often economically rewarded.

This imbalance has global consequences. Mining operations gravitate toward countries with low electricity prices and weak environmental enforcement—such as Kazakhstan, Venezuela, and Laos—externalizing the environmental damage to some of the world’s most vulnerable regions. Yet the profits primarily accrue to international investors.

Section 3 - NGOs: Public Pressure Campaigns Target Bitcoin’s Environmental Impact

Key message: Activist groups are reframing Bitcoin’s energy use as a climate accountability issue and pressuring institutions to act.

While international organizations push for regulatory and fiscal solutions, environmental NGOs have mounted a parallel campaign of public pressure. In March 2022, Greenpeace USA, the Environmental Working Group (EWG), and others launched the “Change the Code, Not the Climate” initiative. Their demand was simple but bold: transition Bitcoin from energy-intensive proof-of-work (PoW) to a more sustainable consensus mechanism. The campaign sought to spotlight the avoidable nature of Bitcoin’s emissions and to hold developers and backers accountable for failing to pursue greener alternatives.

That same year, Earthjustice and the Sierra Club released a comprehensive report, The Energy Bomb, detailing how U.S.-based PoW mining had accelerated climate and community harms. The report gave evidence-based grounding to activists' concerns, documenting local environmental degradation and the resurgence of fossil-fueled power plants to support mining operations. By compiling credible data, NGOs translated what was once a technical debate into a matter of public and environmental justice.

In June 2024, the movement escalated. Greenpeace launched a new wave of ads and editorials condemning major Wall Street firms for funding what it called “one of the most carbon-intensive industries on Earth.” Accusing asset managers of greenwashing, the campaign called for full divestment from PoW-linked crypto ventures. This shift from blockchain developers to financial intermediaries marks a strategic broadening of the pressure front: from code to capital, NGOs are demanding accountability across the crypto value chain.

Section 4 - U.S. and EU: Laying the Groundwork for Climate Accountability Through Data Transparency

Key message: In 2024, the U.S. and EU began taking action on one of crypto’s most persistent blind spots: the lack of reliable, standardized data on energy consumption.

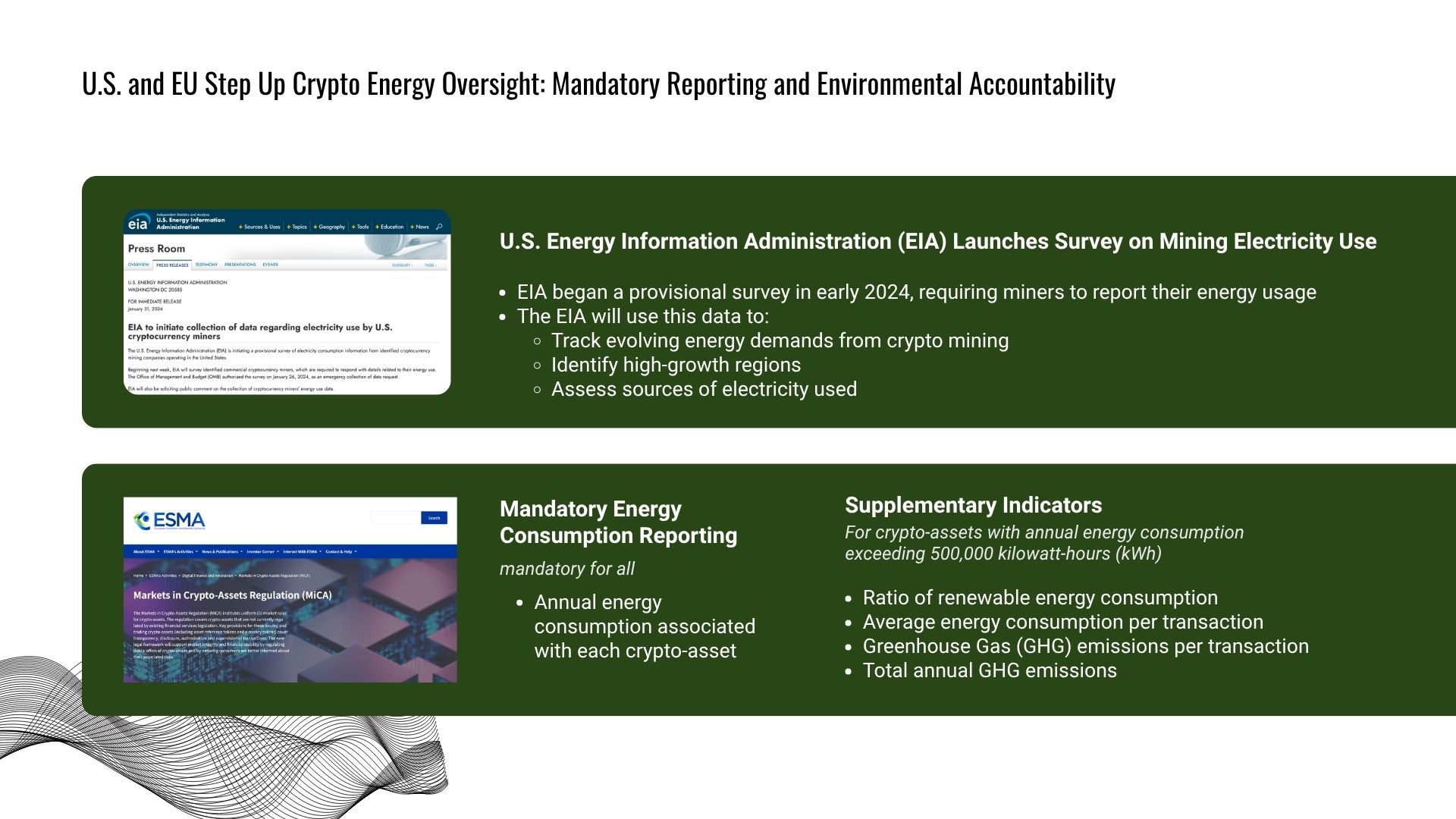

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) launched a provisional survey that compels crypto miners to disclose their electricity use. The objective is not yet to regulate or penalize, but to map the terrain—to understand where mining is growing, how much power it consumes, and what sources (renewable or fossil) it draws from. This baseline is essential before any meaningful climate policy can follow.

Across the Atlantic, the EU has gone a step further by integrating energy disclosure requirements directly into the Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regulation. All crypto-assets must report their annual energy use, and those surpassing 500,000 kilowatt-hours must provide more detailed metrics: renewable energy ratios, GHG emissions per transaction, and total emissions. These measures, while modest, signal a shift from voluntary sustainability claims toward mandatory environmental transparency.

Still, these moves represent only the first rung on the accountability ladder. They are tools for observation, not enforcement. No penalties are tied to excessive emissions; no thresholds are set. But by standardizing reporting and exposing inefficiencies, U.S. and EU regulators are laying the groundwork for what comes next: climate-aligned regulation, targeted taxation, or market-based sustainability incentives. In the evolving “green blockchain” agenda, data is the prerequisite—but not yet the solution.

Section 5 - Governments: Environmental Pressure Adds to the Case for Bans

Key message: While financial and regulatory risks dominate national decisions, environmental burdens increasingly justify restrictions on PoW mining.

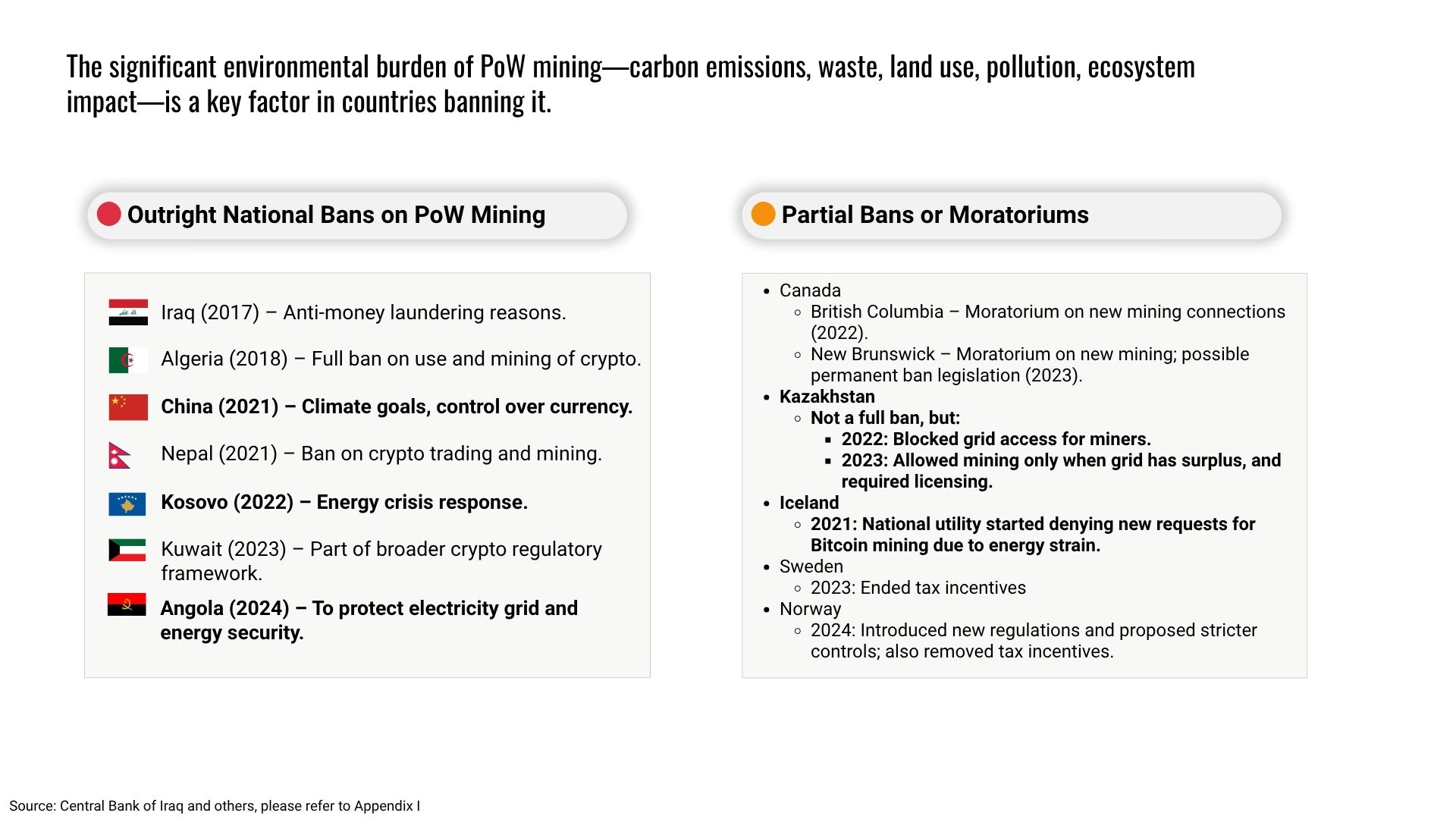

A growing number of governments have taken direct action against proof-of-work (PoW) mining, through outright bans or temporary moratoriums. While financial stability, energy security, and monetary control remain the primary motivations—especially in countries like Iraq, Algeria, and China—environmental concerns are emerging as a key secondary trigger.

China’s 2021 ban notably cited climate targets alongside currency control, while Angola’s 2024 prohibition explicitly aimed to protect grid stability and energy security, both increasingly strained by mining operations. Kosovo and Kazakhstan also referenced electricity strain in justifying restrictions. In some countries like Canada and Norway, environmental impact is becoming more central, with provinces halting new mining connections and rolling back tax incentives on sustainability grounds.

Though not the dominant driver everywhere, climate and ecological stressors are reinforcing state-level skepticism toward high-intensity crypto mining. As energy systems face mounting pressure, governments are starting to treat PoW’s footprint not just as a cost—but as a liability worth regulating.

Section 6 - Industry Efforts: Promising Signals, But Scale Remains a Challenge

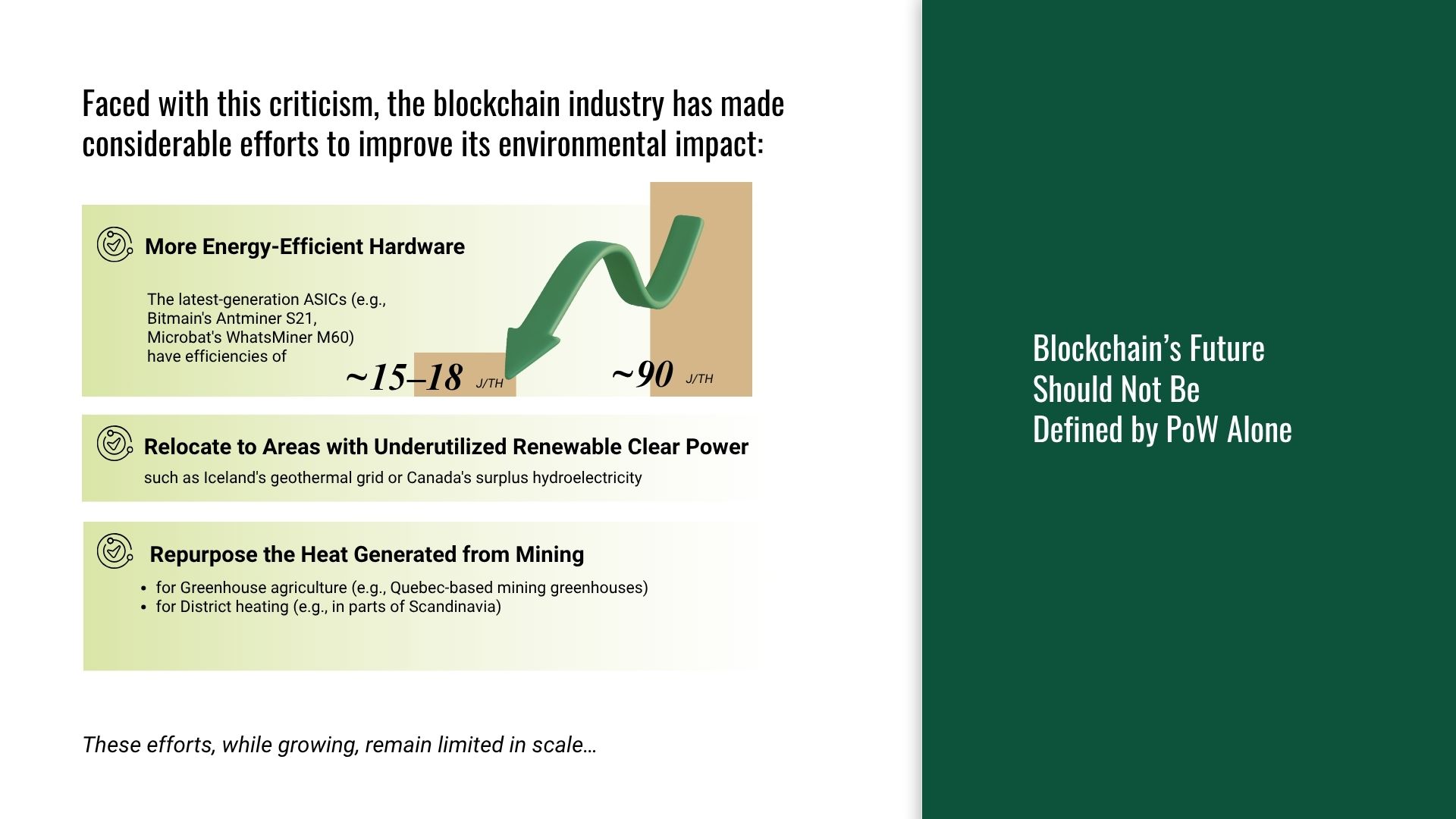

More Energy-Efficient Hardware

Technological advances in mining hardware have brought significant improvements in energy efficiency, with cutting-edge ASICs now operating at just 15–18 J/TH, compared to nearly 90 J/TH in earlier models. However, as discussed in the IMF section, efficiency alone does not drive adoption. In the absence of carbon pricing or penalties for energy waste, many operators continue using older, cheaper, and more polluting equipment—because it remains economically rational. Until fiscal or regulatory pressure shifts the cost-benefit calculus, these innovations will struggle to achieve widespread impact.

Relocate to Areas with Underutilized Renewable Clean Power

Unlike the “energy arbitrage” migration discussed in Section 5—where miners move to low-cost, often fossil-heavy grids—this strategy focuses on reducing emissions by relocating to renewables-rich but underutilized regions, such as Iceland or parts of Canada. These areas often generate abundant clean energy that is either too remote or too costly to transmit to urban centers. By placing energy-intensive operations like mining at the source, this model turns stranded renewable potential into productive use. Still, such opportunities are geographically limited and typically benefit larger, well-resourced firms with the ability to move across borders.

Repurpose the Heat Generated from Mining

Some mining operations are beginning to capture and repurpose excess heat from their machines—particularly for agricultural greenhouses and district heating systems in colder regions. These projects offer a form of energy circularity, transforming a by-product into a public or economic good. While encouraging, they are currently rare and highly site-dependent, requiring close integration with local infrastructure and planning.

Looking Ahead: Promising Starts, But Still Too Limited

The industry’s recent responses—ranging from more efficient hardware to smarter site selection and heat reuse—signal a growing recognition of environmental responsibility. These efforts are technically promising but remain small in scale.

Without stronger external push, they are unlikely to shift industry-wide behavior. Governments should now consider fiscal measures, such as carbon pricing or energy-based taxation, to ensure sustainability becomes a rational economic choice, not an optional upgrade.

At the same time, the industry must reflect on a more fundamental question: is high energy consumption truly inseparable from secure consensus? Proof-of-stake (PoS) has already demonstrated that energy use can be slashed by orders of magnitude without compromising core blockchain functions. While not without trade-offs, PoS and other emerging consensus models offer a pathway to rethink the cost of decentralization itself. If the blockchain community is serious about long-term legitimacy, environmental sustainability must become not a compliance constraint—but a design principle.

References

- International Monetary Fund. “Cryptocarbon: How Much Is the Corrective Tax? (Working Paper No. 2023/194).” https://www.imf.org/… . Accessed: January 15, 2025.

- United Nations University. “UN Study Reveals the Hidden Environmental Impacts of Bitcoin: Carbon Is Not the Only Harmful By-product.” https://unu.edu/… . Accessed: January 15, 2025.

- Greenpeace USA & Environmental Working Group. “Change the Code: Not the Climate – Greenpeace USA, EWG, Others Launch Campaign to Push Bitcoin to Reduce Climate Pollution.” https://www.greenpeace.org/… . Accessed: January 15, 2025.

- Earthjustice & Sierra Club. “The Energy Bomb: How Proof-of-Work Cryptocurrency Mining Worsens the Climate Crisis.” https://earthjustice.org/… . Accessed: January 15, 2025.

- Coinspeaker. “Environmental Activists Blame Wall Street for Funding Bitcoin Mining Emissions.” https://www.coinspeaker.com/… . Accessed: January 15, 2025.

- Greenpeace USA. “Texan Activists to Bitcoin Miners: Don’t Mess with Texas’ Water and Electricity.” https://www.greenpeace.org/… . Accessed: January 15, 2025.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. “EIA to Initiate Collection of Data Regarding Electricity Use by U.S. Cryptocurrency Miners.” https://www.eia.gov/… . Accessed: January 15, 2025.

- European Securities and Markets Authority. “Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA).” https://www.esma.europa.eu/… . Accessed: January 15, 2025.